It can happen to any entrepreneur in any design profession, however, due to licensing requirements, contractual responsibilities, and client-owner expectations, a licensed architect is particularly at risk for liability claims. How can architects prepare and protect themselves before there is a complaint? What is the standard of reasonable care and how is it used to measure an architect’s performance?

Why are Architects targets of opportunity?

Imhotep, allegedly the first architect known by name, is historically recorded as the designer of the step-pyramid building for the Egyptian Pharaoh Djoser, including perhaps, the first known use of stone columns to support a structure. Fast forward approximately 4,680 years when contemporary architecture has become so much more.

Today’s architecture is the art and science of designing and overseeing construction of living spaces, buildings, neighborhoods, communities, and municipalities to add greater value to societies’ growth and viability. Further, sustainability drives design concepts, evaluating and minimizing natural resources as the basis-of-design. These creative efforts influence the construction and operation of new facilities while reducing the environmental challenges of pollution, renewable materials, and conservation of water and energy. However, as architects continue to successfully lead this effort, they could be in the forefront of legal jeopardy.

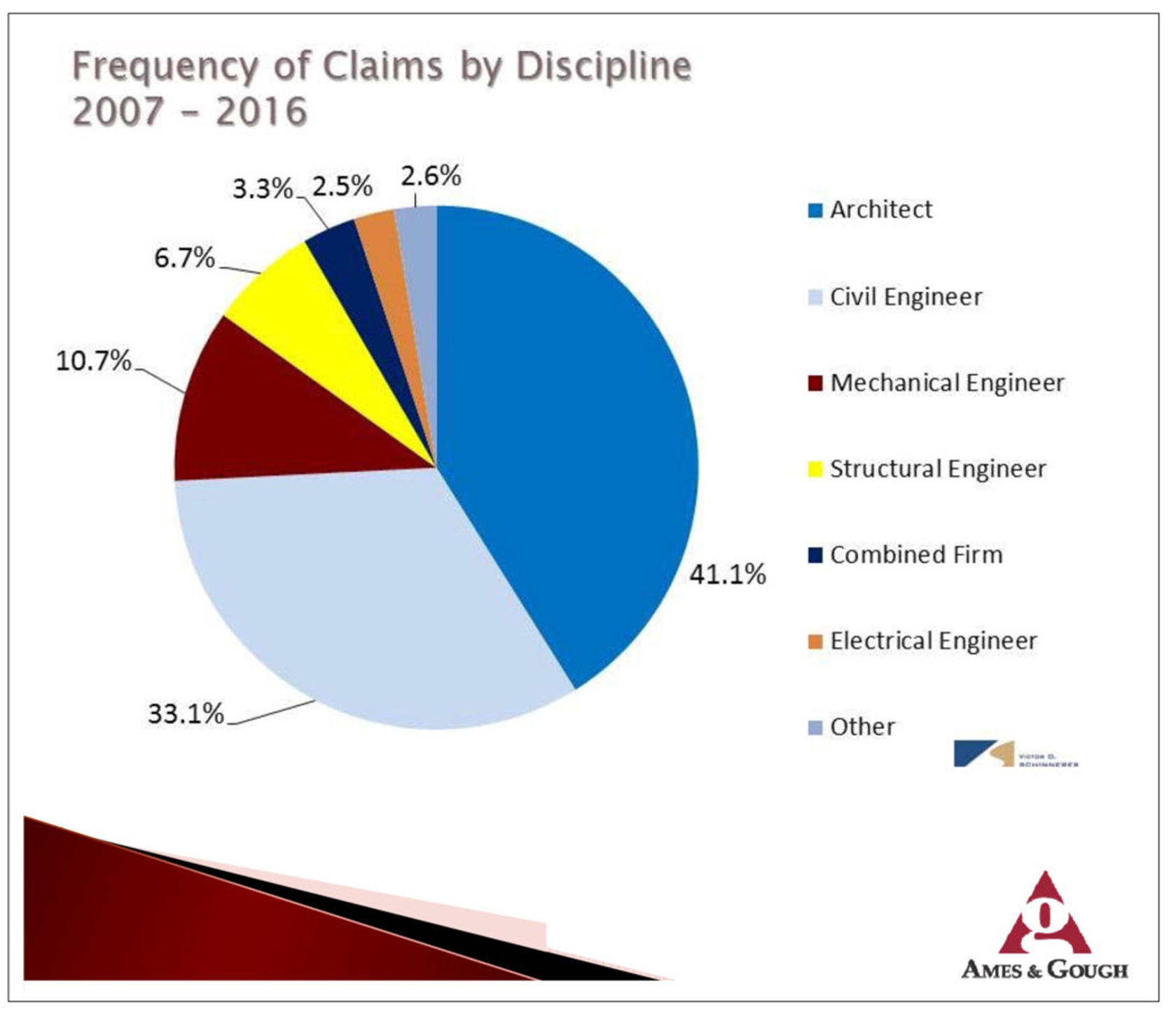

Although architects will continue to be leaders in innovation, adding value to society’s lifestyle viability and sustainable design, trending statistics demonstrate how they continue to be the highest risk targets of the design professions. According to risk management firm Ames & Gough[1], claims during 2007-2016 by professional discipline indicated the frequency of architects being sued was significantly higher—around 41%―than other design professionals at 2.5% to 33.1%.

Having served as an expert witness, mediator, and/or arbitrator on 80+ design/construction dispute cases, it has been my experience that the chance of an architect being drawn into such matters is highly probable. Sometimes the architect (“Firm”) is initially named, or it may take a second round of complaints. But never fear, the architect may then be enjoined in a third-party action.

Because there are so many opportunities for architects to fail, what are some considered conditions of measurement?

- AGREEMENT – The Key to Duty: Architects make written promises to clients. The terms and performance duty under these agreements may be tested by the client-owner and/or opposing parties as a project evolves, and beyond the completed Work. If the agreement is not carefully drafted, as in the AIA family of documents, it may be weak and will be difficult to defend. Simple letters of agreement are loss-leaders.

- CONSTRUCTION DOCUMENTS – Components of Contract Documents: An architect is solely responsible for the preparation of the construction documents (drawings and project manuals) leading to the securing of a building permit. Then a contractor will rely perhaps on the final “construction set” to build the project. Because there is never a perfect set of construction documents, it is reasonable to believe that there may be deficiencies in complying with each-and-every jurisdictional building code. Agreements to comply with “all” building codes, standards, laws, and rules can be a language risk pitfall.

- CONSTRUCTION ADMINISTRATION – Observation and/or Inspection: This continuing service is the point where legal risk probability will be the greatest. The agreement scope of what an architect will or will not do defines the breach of duty measurement of performance. Wording like “observe,” and/or . . .“inspect”[2] for contract compliance, in correspondence or payment applications, etc., raises the bar for an architect’s standard of reasonable care. Any patent and/or latent defects will be generators of a plaintiff’s detailed “rear-view mirror” due diligence of the quality of documentation regarding submittals, on-site observations, substitutions and every word in communications, change orders , field visits, meeting notes, and the project manual.

- TIME – The Equalizer of Risk: Unlike buying a car where the customer purchases a vehicle within days, projects take time, sometimes years. During this time, architects may experience changes in staffing, building codes, and/or financial pressures rendering their businesses ineffective. These events, among others, may influence an architect’s service capability, unknown at the agreement initiation. If any of these issues are not immediately communicated to the client, contractor, and design team, the unintended outcomes may be difficult to defend.

- DEEP POCKETS – Liability Coverage a Desired Litigation Target: Plaintiffs and defendants perceive architects as financially successful with “deep pockets.” If an architect (“Firm”) chooses to not carry professional liability Insurance, it does so at its own peril. Some architects take the position that if there is no professional liability policy there will not be any claim. In a perfect world, that might be the case, but the risk where jurisdictions hold the architect “personally” responsible may predict an approach to include the architect in any legal construction matter anyway.

These practice conditions are inter-related, inter-dependent, and will be measured by a plaintiff and/or defendant through the standard of reasonable care. All parties in any project are at risk, but the architect may eventually be sitting at the defendant’s table.[3]

So, what are the measurement guidelines to meet a standard of reasonable care?

An architect’s performance is generally measured as the degree of care, skill, and diligence for design professionals and may be also couched in terms of “community,” “time-frame,” and/or “circumstances.” However, a broader requisite to consider involves four (4) factors together, each not weighted equally. In this test, the considerations flow from the general to the specific:

(i) Project Type; (ii) Professional Industry Standard; (iii) Jurisdictional Definition of a Standard; and (iv) the Specific Tenants of the Owner-Architect Agreement.

- Project Type:Every architect (“Firm”) eventually develops expertise in certain project types and markets. When a project type and certain design standards have been developed by the architect, it is an easier defense of actions taken by the architect in a project with this demonstrated expertise.

(ii) Professional Industry Standard: “Specifically, the law sets a standard of reasonable care for the performance of architects and, indeed, of all professionals. The architect is required to do what a reasonably prudent architect would do in the same community, in the same time frame, given the same or similar facts and circumstances.”[4]

- Jurisdictional Definition of the Standard:This is always the measurement baseline. In order to protect yourself and your firm, know the jurisdictional statute language defined by the state(s) in which you practice. Each has its own language—or none at all—which defines the standard of reasonable care. For example:

- South CarolinaState Board of Architectural Examiners establishes a standard of reasonable care for the performance of architects (“Firm”). “ An architect or firm shall act with reasonable care and competence and shall apply the technical knowledge and skill which is ordinarily applied by architects and firms in good standing in South Carolina.”[5]

- Florida statutes state it this way; ”Final construction documents or instruments of service which include plans, drawings, specifications, or other architectural documents prepared by a registered architect as a part of her or his architectural practice shall be of sufficiently high standard to clearly and accurately indicate or illustrate all essential parts to which they refer.”[6]

- Specific Tenants of the Owner-Architect Agreement:As important as the statutes are, the actual tenants of the owner-architect agreement are critical, especially if these raise the statutory bar and require a nuanced “higher” standard, like these:[7]

“The architect shall be responsible for ensuring that the Standard of Care practiced by the architect and all subconsultants engaged by the architect to provide design services for the project, shall be that standard of care practiced by other leading architects providing design services on projects of similar size and complexity.”

“Services and Standard of Care. ABC agrees to perform the services in accordance with the customary standard skill and care of ABC’s profession for projects of similar scope and complexity, and in accordance with applicable government regulations. The services will be performed in a manner consistent with owner’s interests and as expeditiously as is consistent with professional skill and care in the orderly progress of such services.”

Unquestionably, any architect’s duty and standard of reasonable care has been breached when the nature or degree of design defects, deficiencies, errors, and omissions negatively impact the basis-of-design and fail to fulfill building code requirements, creates flawed life safety outcomes and future-promised building system performance issues.

CASE STUDY: Standard of Reasonable Care[8]

Abstract: On or about December 2013, a certificate of occupancy was issued for an $18,000,000 residential / commercial mixed-use student housing project. It experienced water intrusion at many balcony exteriors causing water damage to the exterior envelope and potential structural deterioration. Subsequently, a Notice of Claim was sent to various parties including a third party and crossclaim from the contractor to the architect.

To Wit – Negligence: “During construction of the project, the architect of record was retained to render architectural and contract administration services for the owner. The architect of record breached its duty to perform all such work as an architect in a good and workmanlike manner, in accordance with industry standards and applicable building codes.”

PERSPECTIVE

The developer did not bring an action against the architect but filed suit against the contractor. The contractor cross-claimed everyone in sight. So, the architect was required to not only rely on its quality of construction drawings and project manual (specifications), but also its professional service consultant, the structural engineer, throughout the project.

Photos courtesy of Tip Top Construction

ANALYSIS

The contractor entered into an AIA A102-2007, Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Contractor and the Architect, AIA B101-2007, Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Architect. The complaint was whether or not the design and installation of the balcony doors on the exterior walls were code compliant and installed according to contract documents. The balcony patio doors were a building component in the overall weather-resistive barrier building envelope system required by code. The specific requirement for weather-restive protection was identified in IBC, in Chapter 14, Exterior Walls, 1403.2-Weather Protection. Both the architect and contractor had a statutory and contractual responsibility to ensure that this code absolute requiring weather protection was in fact, carried out. The pre-construction basis-of-design was properly represented in the construction drawings / project manual. Also, drawing detail reference was made to flashing guidelines for DuPont flashing systems to be integral after a weather-resistive barrier installation. Specifications provided for mineral-fiber cement siding; weather barriers; sheet metal flashing and trim; and flexible flashing.

During construction, the architect was required to visit the site at intervals appropriate to the stage of construction to become generally familiar with the progress and quality of the portion of the work completed. The architect was not required to make exhaustive or continuous on-site inspections. However, the contractor had a duty not only to the owner, but to follow code requirements regarding means/methods installation of weather-resistant exterior wall systems, and to promptly report any discovered nonconformity of the contact documents with applicable codes.

FINDINGS

Under the general conditions, the contractor’s personnel were responsible for inspecting each stage of installation of the water-resistive barrier components, approving each as complying with the construction documents, before any “following trade” began its work. This pertained to balcony doors, building wrap, metal and flexible flashings, siding, blocking, strapping, and caulking. The purpose of door product approvals and shop drawing submittals was to demonstrate the way by which the contractor proposed to conform to the “basis-of-design” for those portions of the work for which the contract documents required submittals. The architect visited the site twenty-two (22) times over the eighteen (18) month course of the construction. Every visit was documented with observations, opinions, and communication to the owner and contractor in the field, about non-conforming work.

OPINIONS

Although alleged that the architect erred in approving the balcony door product submittal, the architect’s review of the product was not an approval of the exterior water-resistive barrier system assembly. The contractor nevertheless proceeded with its installation means and methods, supporting defective system workmanship, causing water intrusion at door openings, thereby negating any responsibility on part of the architect’s initial product review.

The architect of record met a standard of reasonable care throughout this project, successfully performing to the four (4) realm test. The architect’s services were consistent with the skill and care ordinarily provided by architects to specifically provide a sufficiently high standard of documentation to clearly and accurately indicate or illustrate, all essential parts to which they referred.

CONCLUSION

Experience teaches that design professionals must consider the applicable standard of reasonable care measurements before engaging in any contractual relationship and are advised to seek legal consultation familiar with applicable statutes for design services.

____________________________________________________________________

[1] Benchmarking Studies by Victor O. Schinnerer.

[2] (Author’s opinion) From “observing” to “inspecting” means increasing the bar of duty. When the Architect agrees to “inspect” it agrees to self-determine the frequency to inspect each and every component of a building system being installed-carefully and completely and act on it. This service is different from the lower duty of architects, visiting the project at intervals appropriate to the stage of construction, to become generally familiar with the progress and quality of the portion of the Work completed.

[3] Only true on causes of action by others.

[4] The American Institute of Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice-Fourteenth Edition Chapter 2-Legal Dimensions of Practice – (2.1), pg. 37; The Standard of Reasonable Care;

[5] South Carolina State Board of Architectural Examiners Regulations, amended through February 25, 2010; Chapter 11-12.

[6]Florida Statutes-Title XXXII-Section 481.221 (8).

[7] These are actual clauses from author’s cases, with the architectural firm name changed.

[8] One of the author’s cases.